DAM NATION! THE HASANKEYF TRAIN

September 2007: There had been another court-ordered stay of execution for Hasankeyf. Several had been overturned by the government, so people were wary. Atlas Magazine and Doga Dernegi organized a protest train, the one pictured here. Hasankeyf quivered on the edge of destruction, absolutely unique, a monument to the past, a hope of the future.

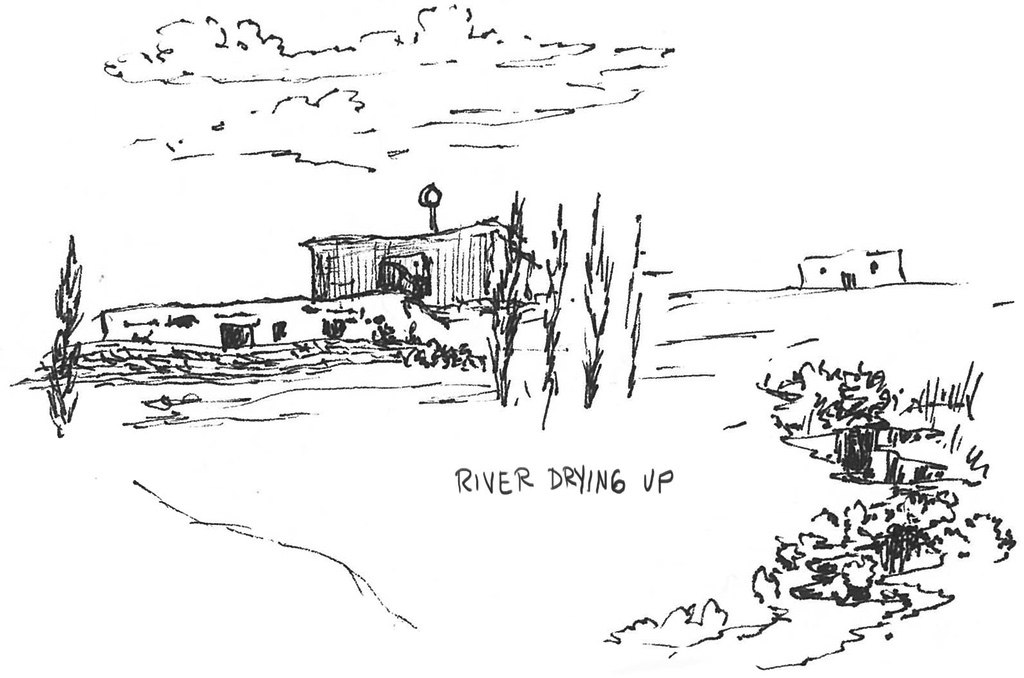

DAM NATION AGAIN! But Turkey is about right now, and dams are the order of the day. Dams are sexy. Lots of water, lots of electricity, lots of jobs, and fast. Detractors say solar power is sexier, that dams dry out the country. There’s a lot of pro-dam noise. Articles sing the praises of the many dams and say they’re creating all kinds of great opportunity. I dunno. I sure saw a lot of dead rivers.

Dam detractors argue that river valleys would, if cultivated, provide more money than the dams, prevent more overcrowding in the cities, and the most fertile and beautiful country in the Middle East would continue to provide plentifully for its people. In Mesopotamia, the origins of civilization would endure as they always have. We could continue to visit and learn from them.

This dam will cost over a billion dollars. It was the approval of the loan of this sum by European banks that inspired the 2007 train trip, one of several. Three hundred and seventy-four Turks and one American traveled with little sleep and no showers to celebrate this diehard ancient town. Future generations may look aghast at the destruction of such a treasure for such a paltry reason. How could people do such a thing? But Turkish people in all walks of life fought long and hard to keep it.

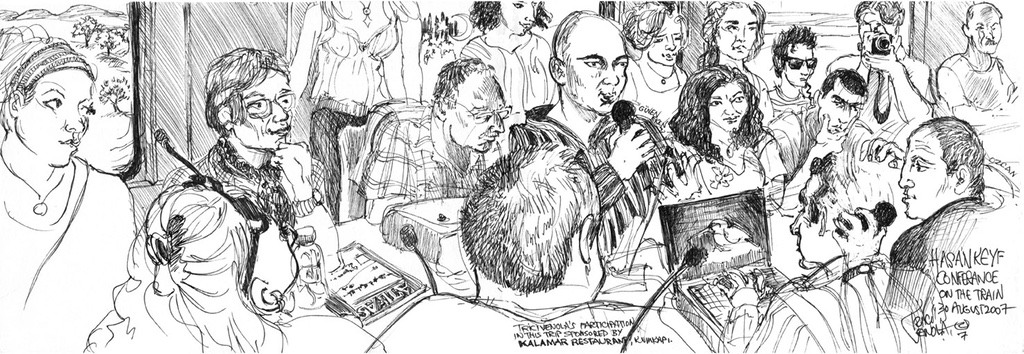

COMMON GROUND The people on the train were educated hip Turks who love antiquities and nature enough to give up a four-day beach weekend for a rackety train with smelly bathrooms, intermittent air-conditioning and only a brief overnight in antiquity before the return. But did we care?

Not a harsh word, and on the next-to-last night, a raucous party stretching through both dining cars with loud singing and people dancing in the aisle and everyone screaming with laughter.

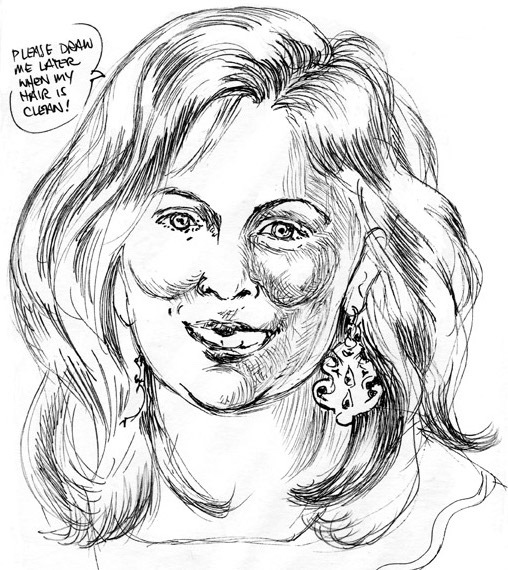

I never met nicer people. This next lady had slept sitting up for days and was still smiling.

You might think that being the only person who couldn’t speak Turkish, I’d feel left out, but no.

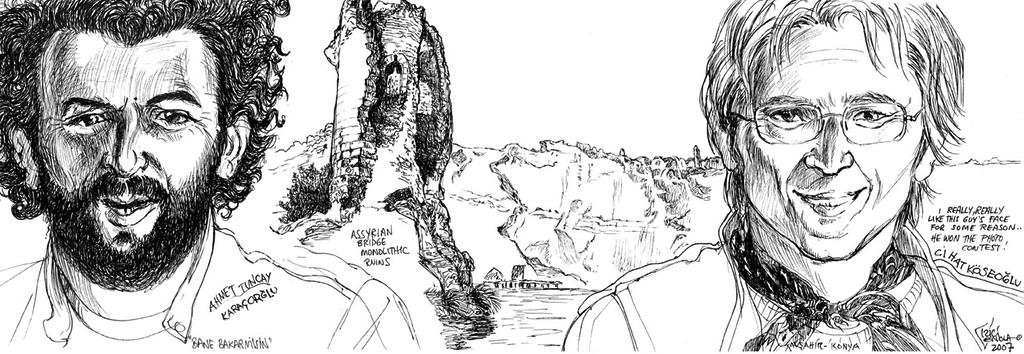

The friendliness of the Turkish people is legendary. Also, Drawing On Istanbul had just come out, celebrating their history and culture, and people made a fuss, made me feel swell. They stood around and watched me draw, and I only wish I had taken fifty copies with me because I sold every one that I had.

FLASH DRAWINGS FROM THE TRAIN

With my scanty Turkish, I couldn’t follow the conference but I drew the passion on the faces as the train roared into the gathering dark. We were all on the Hasankeyf Train, with the two prime movers of this 2007 demonstration to save Hasankeyf from the Ilihu Dam: Guven Eken of Doga Dernegi and Ozcan Yüksek, editor of Atlas Magazine.

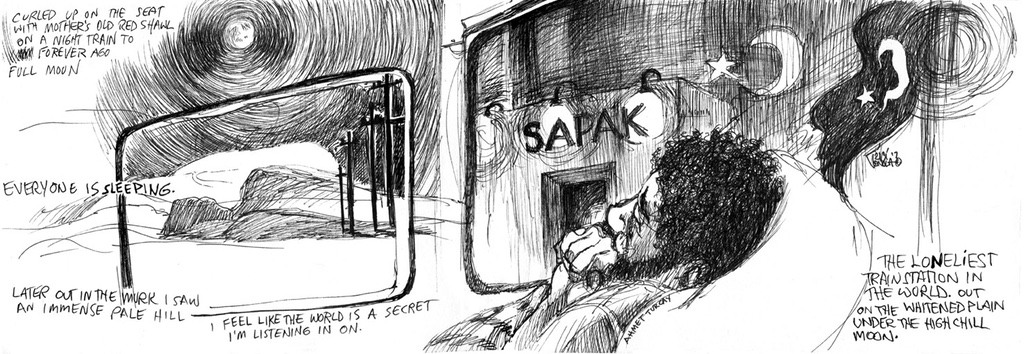

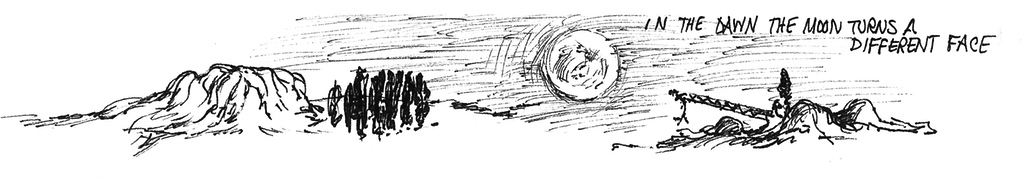

In the middle of the night, indigestion kept me up to see a full moon on the loneliest train station in the world. Was it called Sapak?

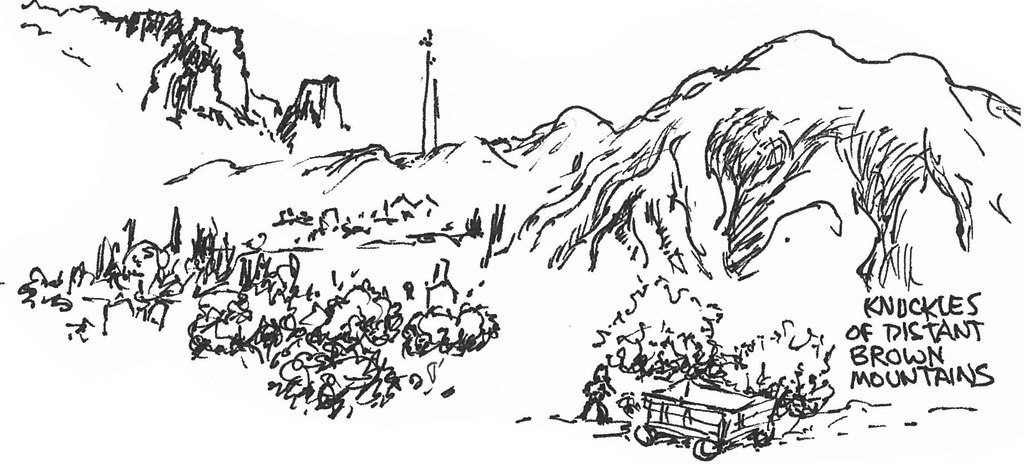

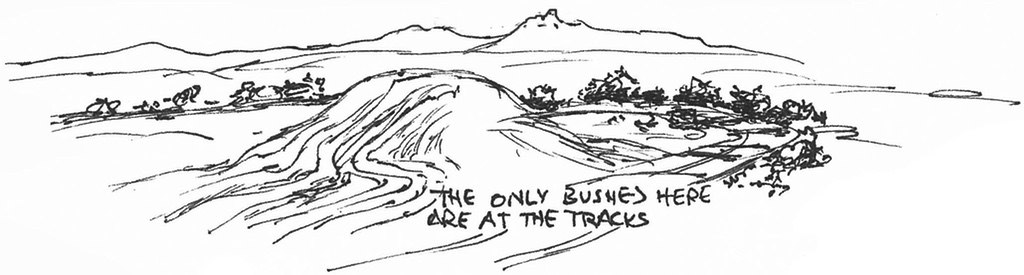

RACKETING ACROSS THE LAND I drew and I drew as rural Turkey flashed by, dozens of tiny thumbnails.

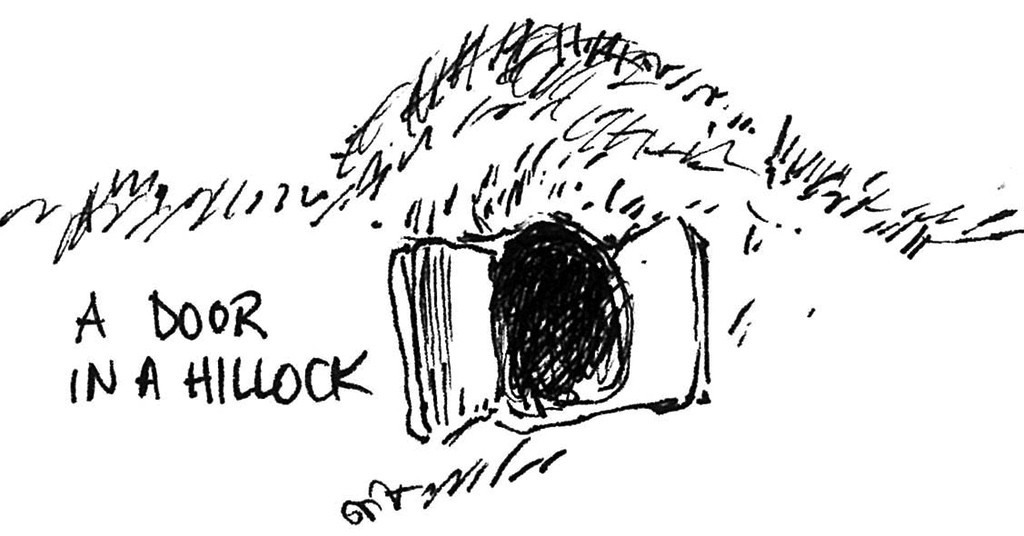

A woman tugging at a sheep, a door in a hillock, a long mud-brick barn, olive trees and grassyknolls and forlorn dusty riverbeds, sad bridges unused; in the distance the bright hard blue of the huge dams.

Toward Malatya, known as Turkey’s breadbasket, the land began to look like the Garden of Eden.

I drew sheaves of poplar trees, tiny houses, orchards everywhere.

The very air was full of essence of apricots. Here, the rivers have water.

Next day: a row of people standing next to sacks full of potatoes in a field, a flock of turkeys, a flat-topped mound with a rectangular cut in it and trucks drawn up: an archeological site. A long line of goats walking along the bottom of a cliff, and in the dawn, the full moon showing a different face.

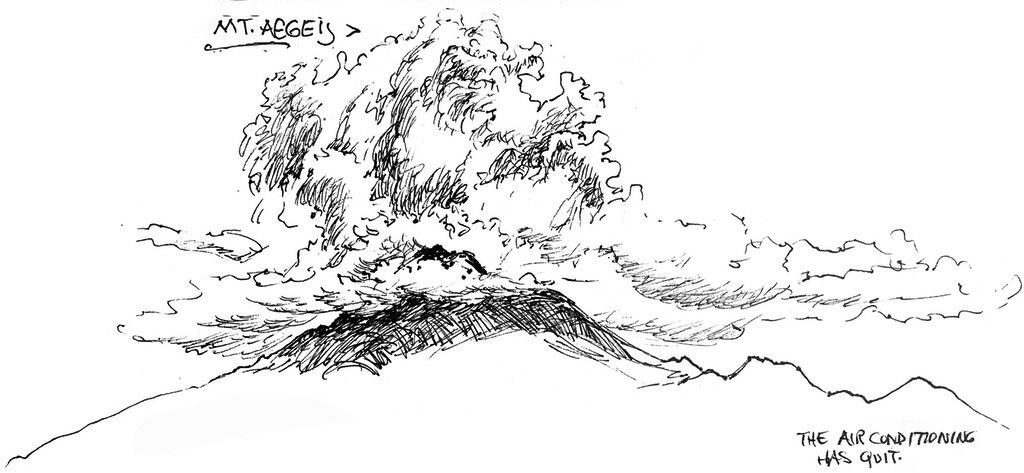

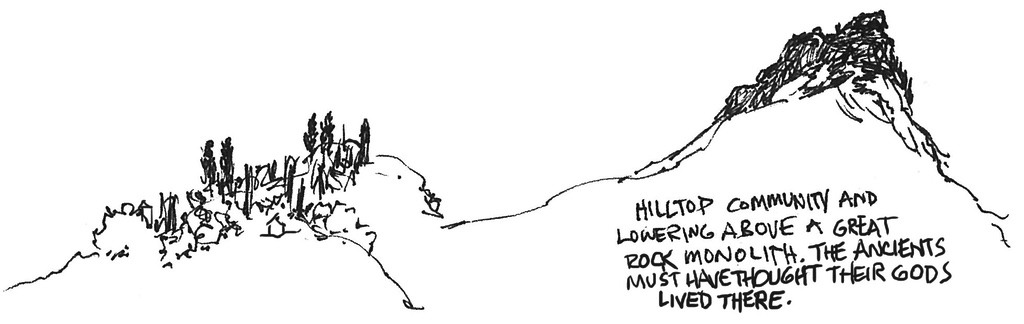

Near Mt. Aegeis, the highest point in Turkey, we racketed past mesas and ramparts of stone jutting out of the dry grassy hills.

A giant, many-pointed black rock loomed near a green hilltop community. Its citizens in antiquity must have believed that the gods lived there.

The mountains grew higher and sharper as we started into tunnels. Spectacular vistas shot past: jagged peaks soaring into the clouds and dizzying glimpses down bottomless canyons covered with cedar trees.

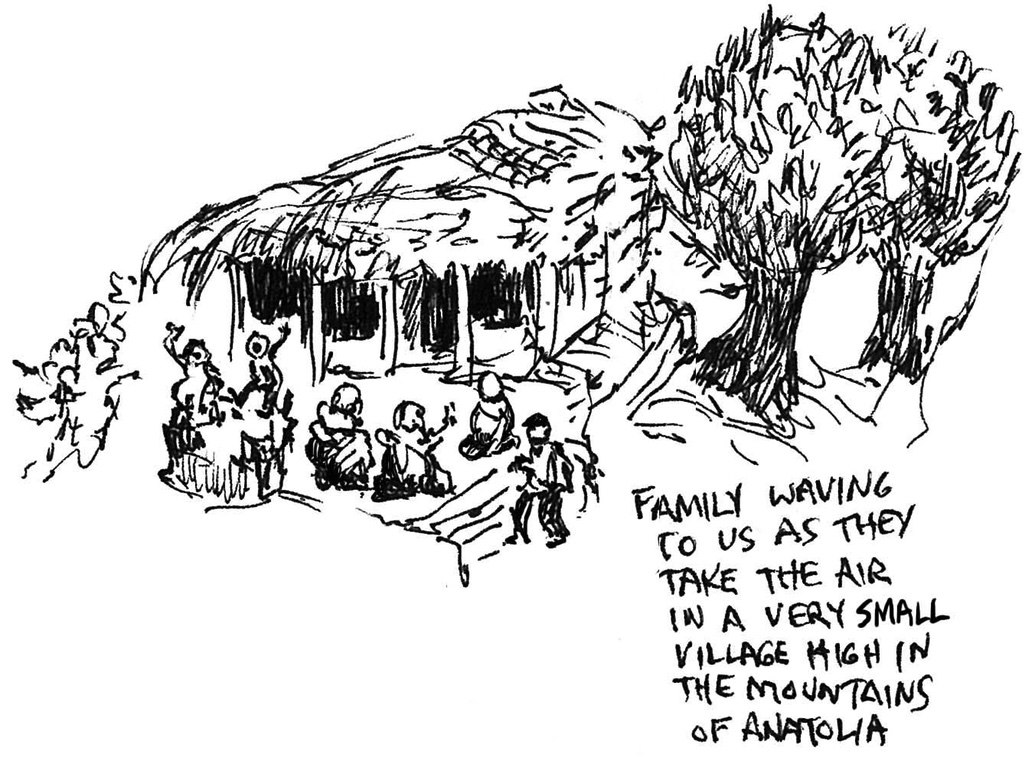

Stunned, I stopped drawing and just gaped along with everyone else on the train. None of this can be seen from the road, only the rails. A sudden thatched roof on a terraced hodgepodge of brick and wood near some olive trees, and the whole family out taking the sunset air, a little boy and girl up on a cistern, waving.

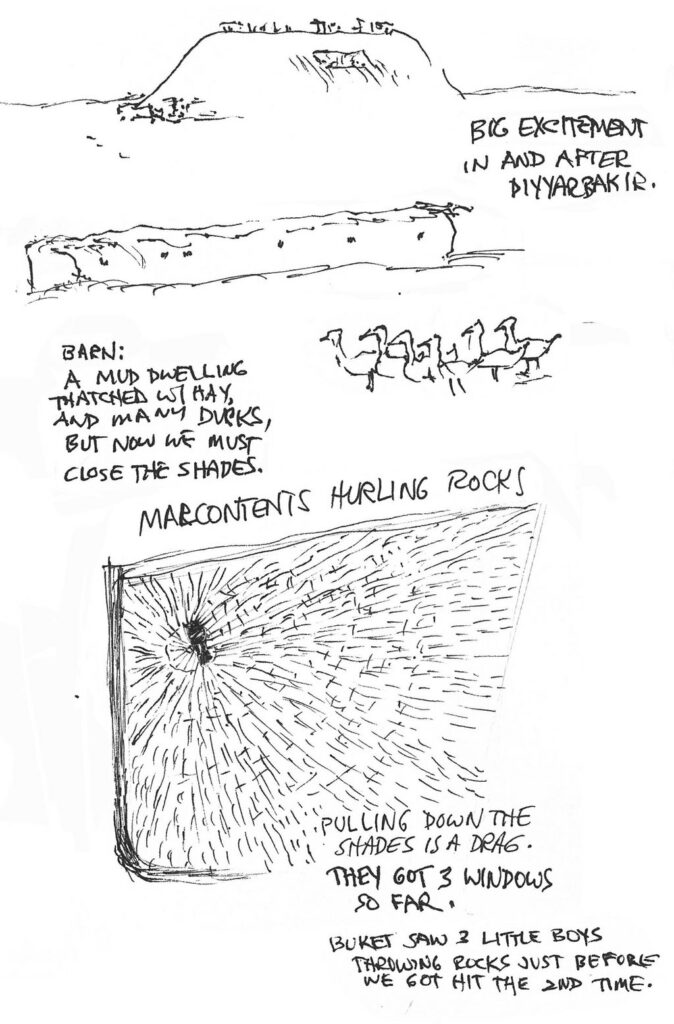

Near Diyarbakir, the copper in the hills shadows blue into the rust of the mountain towns. We had been warned that malcontents might attack our train in this area, and they did: several windows were hit with rocks, the shatterproof glass spiderwebbed behind the posters that said THE HASANKEYF TRAIN.

My new friend Buket (pronounced Boo-Cat) saw the malcontents: three little kids. In the dining cars everyone drank coffee and tea and ate kebap and grinned at the waiters and charged their telephones at the outlets. By now many of us women had bright scarves over our flat sweaty hair. By the end of the trip these had bloomed into fantastical headdresses.