Drawing in the Dark

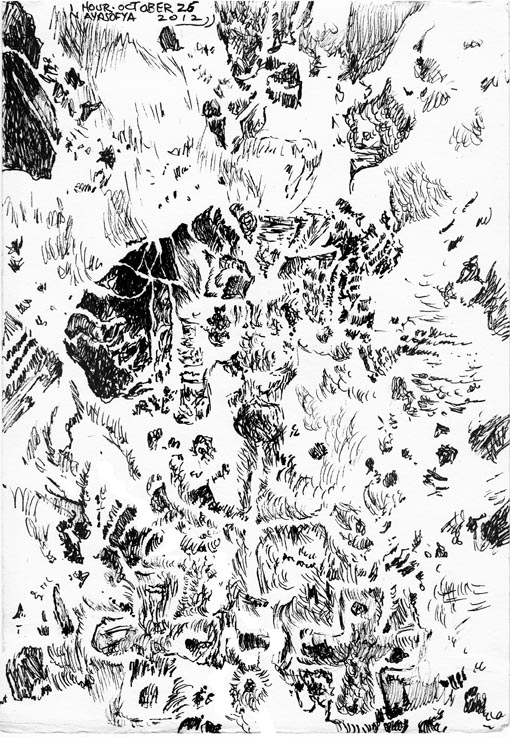

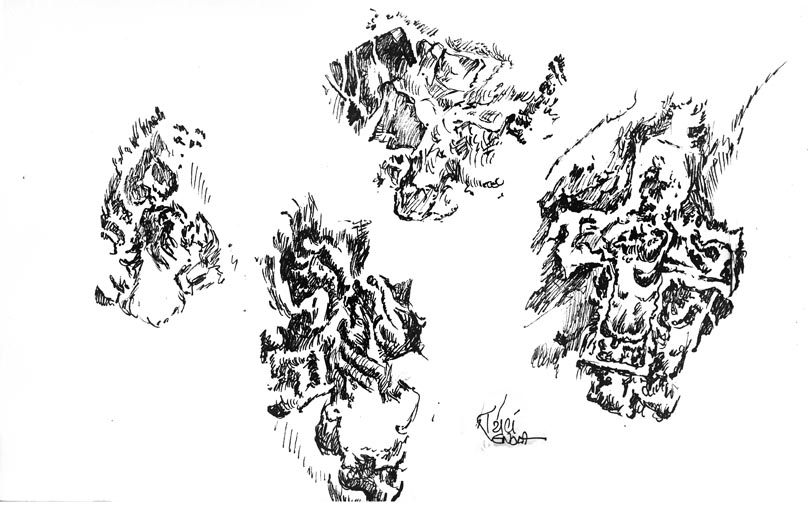

Next thing I knew, I was sitting for days in the dark behind a pillar with a flashlight stuck in my hair, telling a diverse parade of perfectly fascinating people from all over the world about the Crusader Crosses and the Fourth Crusade. A guide came along and excitedly told us that in 28 years he’s never seen these particular ones, and that I must be lucky. And how! I get to be here and draw this:

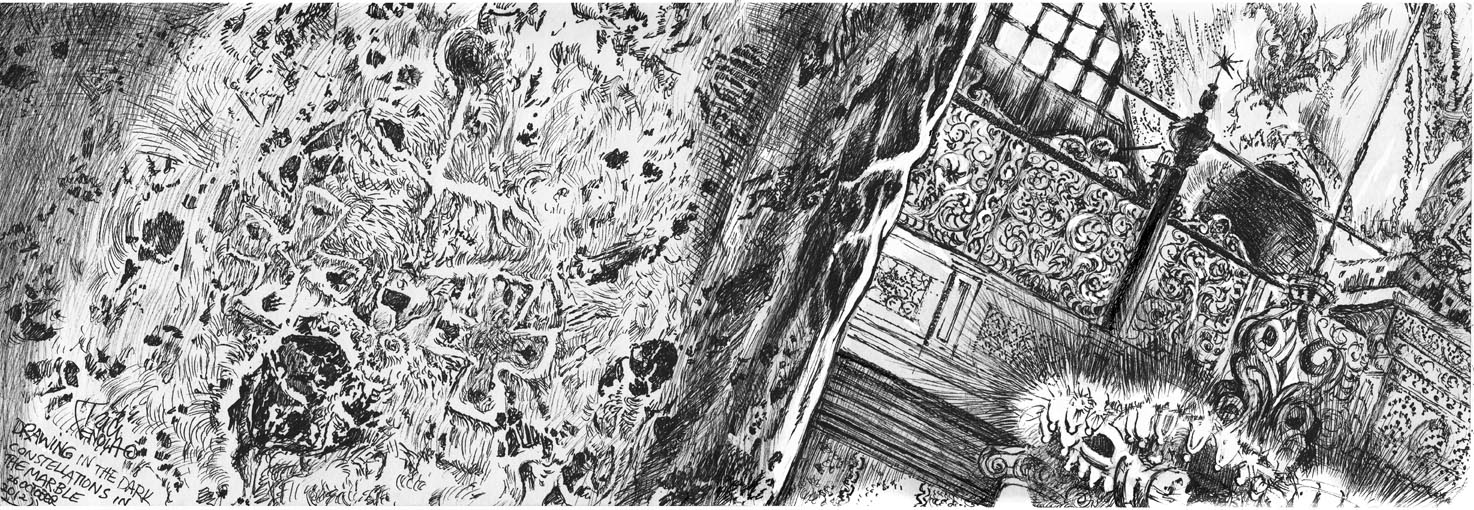

I slaved over this drawing and despaired of ever getting it right. There’s so much detail, and it’s all so dim. It took about fifteen hours. The crosses here have no lead and are far down on the wall side of the pillar. I found them by feeling around and using my little flashlight. Notice that there are bits of the dark shiny original surface left on the crosses as decoration, and that the two crosses are linked by a bit of it. Like two names. Are we looking at a Crusader Bromance here? Even a Romance is possible: ancient Romans had the canonized gay soldier couple Ss Sergius and Bacchus as patrons. Why not Crusaders?

We’ll never know. All that is certain is that someone carved these, and took the time to do it neatly and carefully. Here’s a shot of the entire composition, which I didn’t notice until well into the drawing. There are four: our two linked ones at the bottom, a deeply incised stick cross in the middle, sort of pouring out of a very deep hole, and the top one which is forever just coming into being out of the marble. I find this one magical.

“Politicians, ugly buildings and whores, all become respectable if they last long enough,”said John Huston’s raddled old crook in Chinatown, and so it is with graffiti.

Can worship create an energy? Hagia Sophia, St John’s, the Temple of Artemis, St Savior in Chora, Rumi’s Tomb in Konya, Baalbek in Lebanon– all are palpably holy places, whether ruins, museums or adaptations to another religion. The columns from Pagan temples still reverberate with worship to the ancient gods, although they’ve been holding up Ayasofya for 1500 years. Worship is a powerful force, and although the name of the Deity changes I believe the force remains, singing down through the pillars through the massed energy of millenniums of temples here on this rock sacred from the beginning of time. So what’s the story with Christian crosses carved as graffiti in a Christian church? Why do I think these are from the Fourth Crusade?

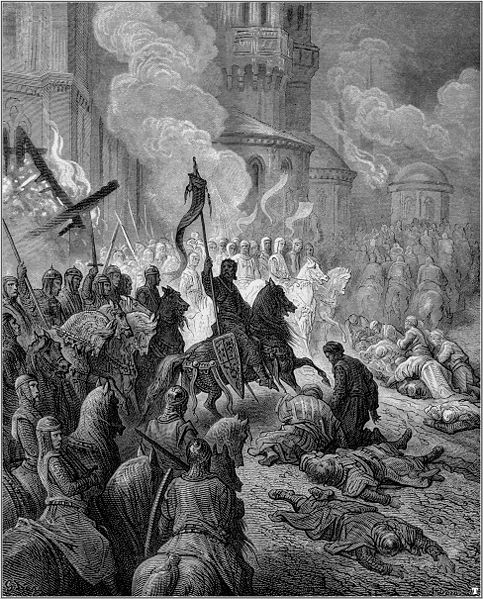

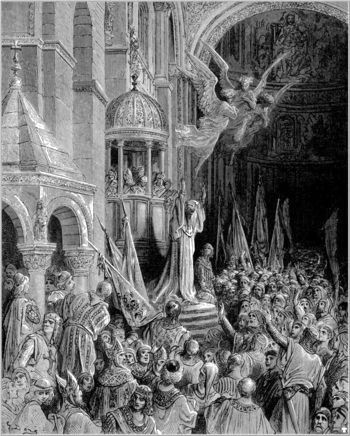

Hagia Sophia was consecrated in 537. Until the rape and sack by Crusaders in 1204, no hostile armies succeeded in getting into the city. It’s unlikely that anyone would have cut crosses during that time. In the late 8th century the Iconoclasts, starting with Emperor Leo, destroyed much of the pictorial art: mosaics, bas-reliefs, everything. But crosses were allowed to remain. Graffiti ones, though? This one is right out in front of the altar!

You can see in the photo below that another cross was started. Somebody swinging an axe, chopping away…

Carving with a knife into marble is not so easy. One must devise a chisel effect and bash at it with…what? A mallet, a mace? Lean into the edge with all your might, again and again. Noise, fuss, swearing, leaning there on your cutting device and scraping. Not a light undertaking, and nothing furtive about it. Here are three columns in a row, each with a cross in the same place.

From 1453 until 1931, Hagia Sophia was a mosque. Mehmet the Conqueror, in 1453, refused to burn it. Instead, his men built a minaret and amputated the arms of every cross they could find. A Western tourist visiting the Ottoman empire might have succeeded in furtively scratching one cross over in the shadows, but banging away, cutting deep into marble floors and pillars right out in the nave, making all these and more?

Could the crosses, similar in size and shape, have been made after the Republic? Hagia Sophia has been a museum since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk declared it one in 1935. It was closed for four years prior to that. It’s barely possible that some Christian fanatic was working there alone at night…but I doubt it. It’s much more likely to have been then that some insect cemented over several crosses, at the front of the nave and on a few of the pillars. These boneheaded attempts have the look of some excised crosses upstairs, in which the axe cuts faithfully echo the cross shape. Someday a method may be found for dissolving cement without dissolving the stone underneath, but until then I can only long for a chisel.

Nope, not likely during the Ottomans, nor after the Republic. Had to be Fourth Crusaders. Here’s why.

I love reading these.

Reblogged this on Drawing On Istanbul.

I love Istanbul and these drawings bring to me the need to go back and see the city with Trici’s eyes.

Fantastic!