A PAGAN FELLINI NIGHT Back on that first trip in 2005, Cynthia and I returned from Ephesus to discover that a big soccer game had taken over the town. We dressed in our trailing scarves and earrings and went out to dinner. All the way out at the edge of town was the marsh with the one Artemis pillar and a lumpy old weedy hamam. Beyond the fence was a dark poor area, just little cement houses, all deserted with the game on. At the very end of town was a triangular lot at the end of two streets edging the marsh. There was a cafe, lit and open and no TV, with one woman who made us dinner.

We sat there under the grapevines as darkness came slowly down on the town. Two men sat down nearby. One joined us, speaking with Cynthia at length in French about their respective youths in Paris. Something creaked in the quiet, and out of the dark trundled a popcorn vendor. “It’s a Fellini movie,” someone said. We stayed for hours, drinking coffee and red wine, the dark silence punctuated by an occasional car full of screaming soccer fans roaring out of the dark and away. A rose man materialized. The man who spoke French had a friend with a huge mustache, who jocularly gave us each a longstemmed, strong-scented red rose.

At last we took our roses and our leave and wandered home through the dark streets, up the hill past the rampart-like gate leading to the ruin of St John’s Basilica, and started down. At the base of the hill was the road, and across it the town entrance, a huge modern circular stone fountain with a big arch and a giant kitsch reproduction of the Great Artemis. We heard it first, a pounding scream coming from the crowd next to the fountain. As we came down the hill the noise became deafening. Close up it was a Bacchanal.

In ancient times people would fling themselves into a sexual frenzy in the names of their deities: Osiris, Dionysius, Demeter. When Christianity took over, the people continued to dance in worship. Nothing could break them of it. After six days of backbreaking labor the serfs would dance on the seventh, and they would do it in the churchyard. Passion and worship, forever married. Now we looked down on a chaotic festival of screaming young men dancing to pounding music simulcast from the stores in the street. Flung water glittered in a strobe light. The dancing became wilder as people fell and leaped into the fountain. They took the winning soccer colors—yellow and blue– and wrapped them around the hips of the Great Goddess and shimmied them. One pubescent kid saw us watching him, strutted shirtless with his chicken chest stuck out and his wet pants plastered to him, stood at the huge stone back of the goddess facing us, applauding across the water, and danced like a stripling priest. Cynthia and I stood at the lip of the fountain, encouraging the young girls, but in the end, as so often, we were the only women dancing.

In the fairy tale, The Marsh King’s Daughter found faith, which unified her lovely form and spirit. She ascended in joy to the Kingdom of Heaven, leaving only a withered lotus flower behind. Cynthia is slipping away now I am told, in a final coma across the world in Hawaii, and I write this in the winter’s dark of Istanbul years later. The Aloha Blonde is taking her roses and her leave, those cat eyes and the husky voice murmuring French to some eternal young man. She is flying with the storks, her glory trailing behind her, and I’m writing this for all of us left at the party.

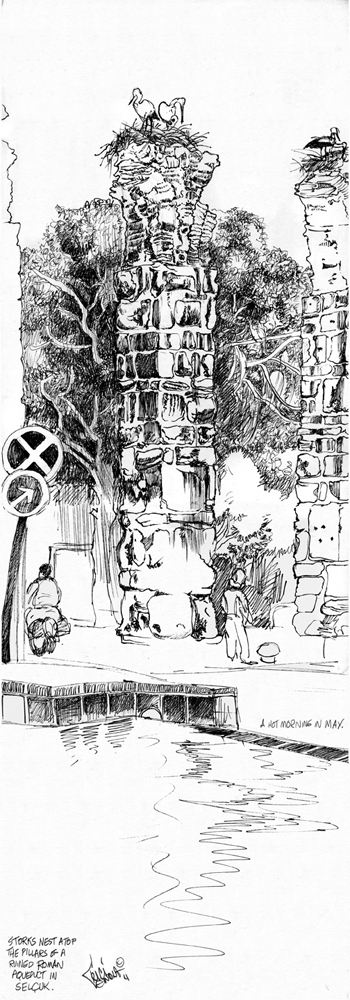

Updated in 2022. All drawings Plein Air, ©Trici Venola. All fairy-tale paraphrases are from The Marsh King’s Daughter, by Hans Christian Anderson. Lewis retired from the US Diplomatic Corps to Mt Shasta in California, where he continues to spread delight and do good works. A few years back, Sister Mary Emmerlach was canonized. Cynthia’s husband Hakan still runs a business in Maui and on the US mainland. Cynthia died in 2012, of breast cancer. She and Lili had been all over the world, trying to find remission. After she died, her friends made a great fire on the beach in Maui and danced around it, scattering her ashes to the ocean winds and singing her way out of the world. I still light a candle for her every Sunday here in Istanbul. She’d like that.

END